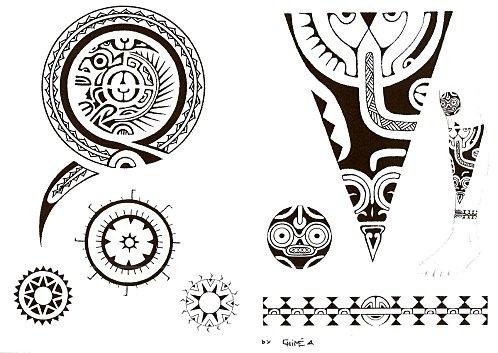

tatouage maori

Tattoo arts are common in the Eastern Polynesian homeland of Māori, and the traditional implements and methods employed were similar to those used in other parts of Polynesia (see Buck 1974:296, cited in References below). In pre-European Māori culture, many if not most high-ranking persons received moko, and those who went without them were seen as persons of lower social status. Receiving moko constituted an important milestone between childhood and adulthood, and was accompanied by many rites and rituals. Apart from signalling status and rank, another reason for the practice in traditional times was to make a person more attractive to the opposite sex. Men generally received moko on their faces, buttocks (called raperape) and thighs (called puhoro). Women usually wore moko on their lips (kauae) and chins. Other parts of the body known to have moko include women's foreheads, buttocks, thighs, necks and backs and men's backs, stomachs, and calves.

Originally tohunga-tā-moko (moko specialists) used a range of uhi (chisels) made from albatross bone which were hafted onto a handle, and struck with a mallet. The pigments were made from the awheto for the body colour, and ngarehu (burnt timbers) for the blacker face colour. The soot from burnt kauri gum was also mixed with fat to make pigment. The pigment was stored in ornate vessels named oko, which were often buried when not in use. The oko were handed on to successive generations. Men were predominantly the tā moko specialists, although King records a number of women during the early 20th century who also took up the practice. There is also a remarkable account of a woman prisoner-of-war in the 1830s who was seen putting moko on the entire back of the wife of a chief.

Originally tohunga-tā-moko (moko specialists) used a range of uhi (chisels) made from albatross bone which were hafted onto a handle, and struck with a mallet. The pigments were made from the awheto for the body colour, and ngarehu (burnt timbers) for the blacker face colour. The soot from burnt kauri gum was also mixed with fat to make pigment. The pigment was stored in ornate vessels named oko, which were often buried when not in use. The oko were handed on to successive generations. Men were predominantly the tā moko specialists, although King records a number of women during the early 20th century who also took up the practice. There is also a remarkable account of a woman prisoner-of-war in the 1830s who was seen putting moko on the entire back of the wife of a chief.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home